Attention follows intention

How fatigue reroutes the mind

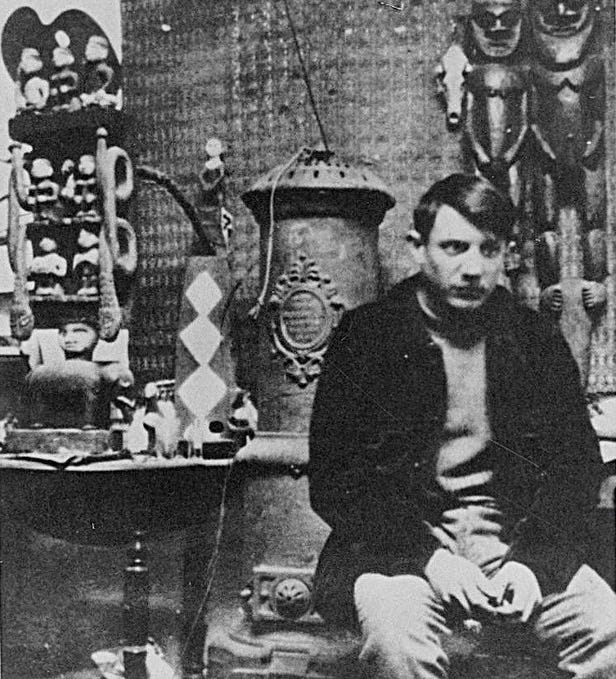

Picasso in his studio in Montmarte, 1908. Wikimedia Commons.

“Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act.”

-Pablo Picasso

Last night I returned home late from traveling, over-caffeinated and a little too wired to sleep. Throughout the night I tossed and turned and in the morning woke up feeling groggy and unfocused. I deliberately avoided checking my sleep tracker, knowing that the data would only confirm what I already felt. I knew it would shape my mindset in a way that would drain motivation rather than build it.

I intended to start the day with purpose and dive straight into writing. But before I opened the Word doc, I checked three different news sites to see what I had missed in the last 24 hours. I then looked through my email and caught up on some lingering emails that I had set aside. Then I unpacked my computer bag, throwing away garbage. Finally, after all these distractions, I decided I had had enough and turned to writing.

This is what happens when attention doesn’t have a clear target.

Attention is goal-directed. If our goals are clear and specific, like working on a book chapter, then that’s what we focus on. But if our thinking is muddled and our goals are far away, then our attention shifts to whatever is easiest or most immediately rewarding. That’s exactly what happened to me. Instead of thinking of my main goal of writing, I defaulted to low-effort short-term goals like checking news and email, cleaning out my bag.

Alertness and motivation also shape attention. When we’re fatigued, we lack the cognitive resources needed to hold higher-level goals in mind. Our minds wander more easily, and our priorities quickly dissolve.

Neuroscience explains why. Sustaining a high-level goal relies on executive function, located primarily in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that holds plans in mind, filters out distraction, and keeps impulses in check. When we’re tired or stressed, executive function weakens. Control shifts to more habitual systems that favor immediate reward. The brain moves from long-term strategy to short-term payoff. It’s not a moral failure on our part, it’s biology. In sum, it requires effort to keep our goals in mind, and our goals direct where our attention goes.

The relation of goals and attention is more nuanced though. We move among different modes of attention throughout the day as our energy shifts and environments change:

Automaticity. Sometimes we respond to cues that evoke habitual routines. When you wake up and see your phone on the nightstand, the sight of your device triggers a wakeup routine of scrolling and you do this without conscious intention. When I opened my laptop, checking email and news was automatic.

Reactivity. At times we pursue short-term goals. When we’re reactive to the demands in the environment, like with pings and notifications, our intentional higher-level goals are overridden by such “in-the-moment” activities and distractions. We multitask, switching our attention to whatever arises. We can also pursue short-term goals when we’re fatigued or bored, such as watching short-form videos.

Agency. This is when our attention is oriented to higher-level goals. We focus on doing those things to achieve the goals. We’re also guided by an awareness of our cognitive resources. We know when to act and when to rest so we don’t get overextended.

Technology of course plays both sides. It can support agency and help us pursue our goals, such as through productivity software. But technology can also undermine our goal-driven attention by presenting us with easier and often more interesting alternatives to look at online. These provide us with short-term gratification, as opposed to a delayed and far greater reward for reaching a higher-level goal.

Research shows that when goals are specific, they can strengthen focus. In one study, participants who were told to react to a probe in less than .43 seconds had longer sustained attention compared to those given a vague goal to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. We’re more motivated when a goal is concrete. It helps explain why games are so engrossing: the goals are specific and continually reinforced (“earn 100 points for killing each zombie”). I could apply the same principle to my writing: “Write two pages before taking a break.”

In a study led by Alex Williams at Microsoft Research, on which I collaborated, we found that when people define their task goals the night before, and then reviewed them first thing the next morning, they stuck more closely to their goals. People spent more time on productivity apps the first hour of the day, compared to when they didn’t articulate their goals. This study further supports the idea that keeping goals in mind helps us focus.

We know that setting goals matters. But why it’s important is that goals direct attention. They act as signposts that orient us toward purpose. They make our actions intentional and protect us from the gravitational pull of distractions. Our attention is quite malleable, and without clear goals our attention drifts like a sailboat carried by currents with no rudder. Goals stabilize us, giving our minds a direction.

Attention is a form of power. We own it, but in a world eager to choose for us, the challenge is for us to learn how to harness our attention and steer it where we want it to go.

**************************

You can read more about our attention and how we can stay on track to meet our goals in my book Attention Span, now in paperback with exercises.